Today, February 2nd, is World Wetlands Day! For many of us, they are probably habitats that we pass by without fully acknowledging them. They are likely not green spaces that we actively seek out (unless you are a birder). And even though I have lived near one for years, I do not think I fully appreciated how truly magical they can be until I started to learn more about them. So let’s dig in, but first…

What is a Wetland?

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), a wetland is land that is saturated with water, or essentially exactly what its name implies. Some wetlands are present year-round and often adjacent to larger bodies of water, like the ocean (marine or estuaries), lakes, or rivers/streams. Other wetlands form seasonally, like vernal pools or seasonal lakes. Both play key roles in the health of our planet, which brings me to…

Reason #1: Wetlands help store water and carbon

While these reasons are in no particular order, I put this one first because I didn’t realize it before taking the time to learn more. Without wetlands, planet Earth would not be the same at all. Here are just a few key services they provide –

1. Wetlands help store water – When water moves quickly through an area, it can cause a lot of damage and transport material long distances. The process of down-cutting, where water cuts down through soil to bedrock, can detach a river or stream from its floodplain, making it less accessible for humans and other animals. It can strip away the nutrient-rich topsoil that we rely on to grow crops and for other native plants to grow as well. But, water moving through a wetland moves much more slowly, allowing more of it to seep into the groundwater that many rely on for drinking water.

Because wetlands store water and are often located in lower elevation areas, it is not uncommon for them to be drained for use in irrigation or to make way for housing or other human uses. If the water is recharged on a regular basis, this would cause less harm, but if the native plants are removed to make way for pavement, they are no longer able to perform this important role.

2. Wetlands filter water – Wetlands act as nature’s scrubbers for water, helping to remove nitrates and phosphates from fertilizers, as well as heavy metals and other pollutants. In the case of nitrates and phosphates, these chemicals can bind to to root structures of wetland plants like rushes and cattails. Since the water is moving more slowly, these materials are more likely to filter out into the sediment as well. In fact, wetlands can remove as much as 90% of these materials from water before it reaches a major waterway. When these compounds are removed, it also helps limit the growth of harmful algae and cyanobacteria that make waterways less safe for us and the animals who live nearby to drink, swim, or live in.

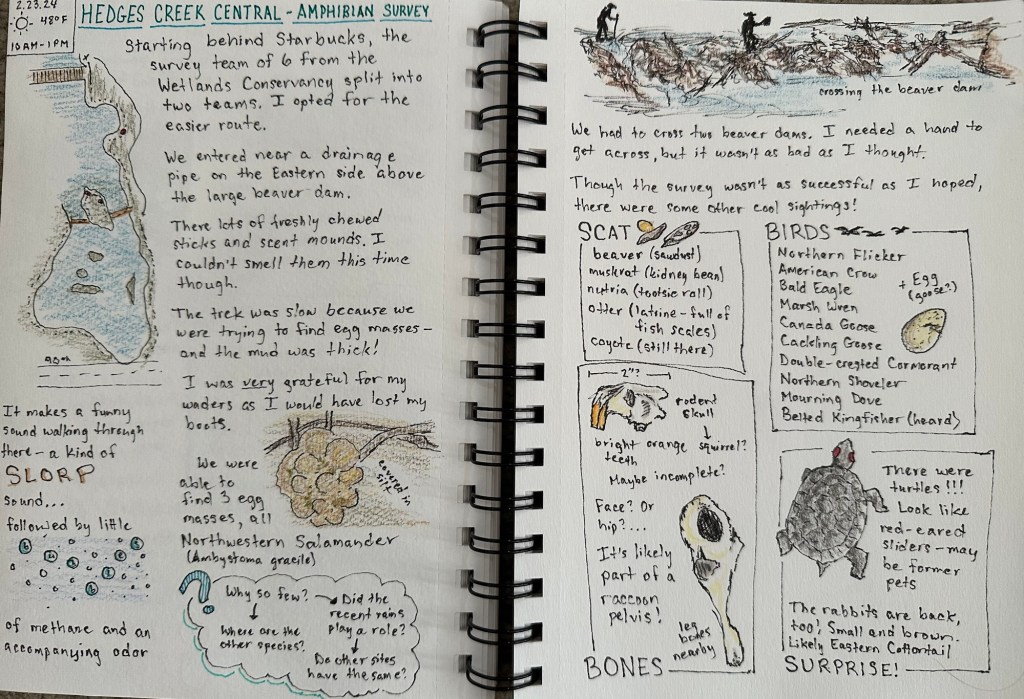

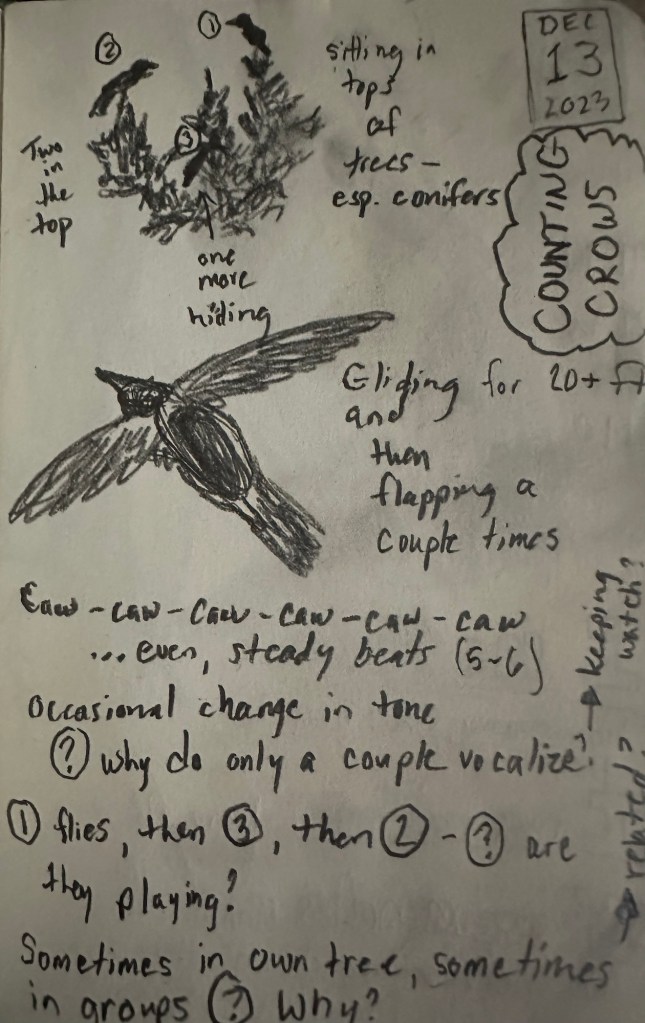

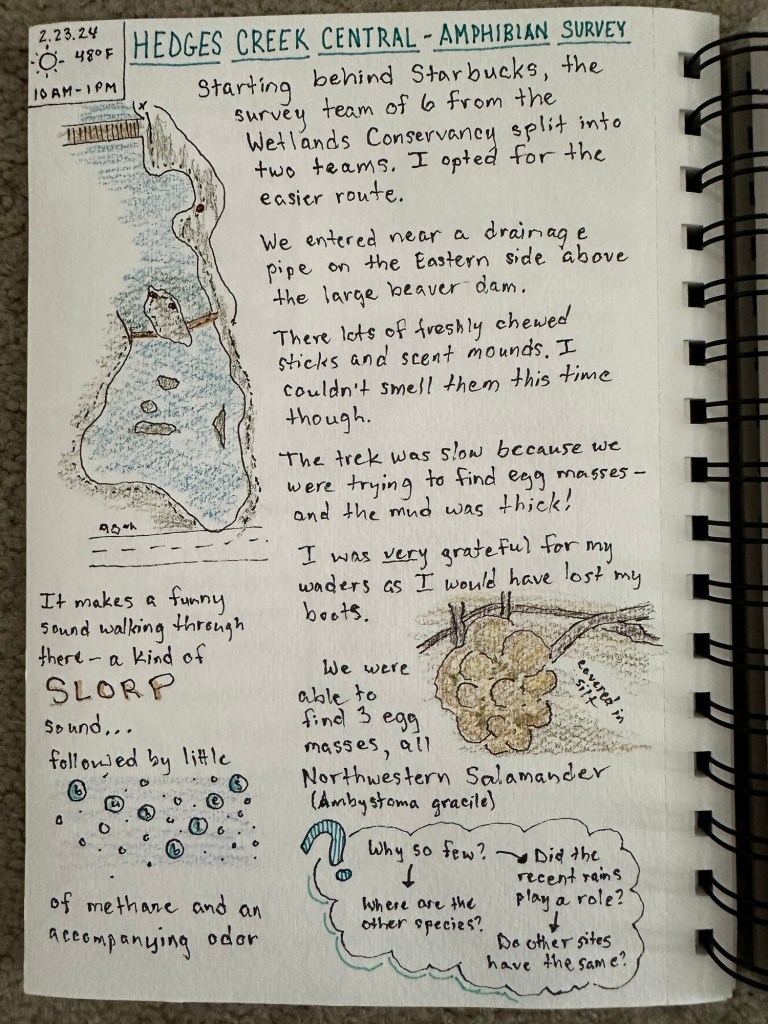

3. Wetlands help store carbon – If you have ever taken a walk through a wetland, particularly on a warm summer day, you may have encountered evidence of this function. The rushes, sedges, and grasses help to trap carbon in their structures. When these eventually break down, much of the carbon is then stored in the soils of the wetlands though small amounts of methane can bubble out when disturbed when you walk through this habitat. These gases can give wetlands a rather distinctive odor. But this process of trapping carbon means that it is kept out of the atmosphere and thus less likely to further climate change. In fact, in tropical settings, wetlands may be three to five times more effective at storing carbon than the same area of tropical forest (NOAA).

Reason #2: Wetlands help prevent flooding

I know what you might be thinking – how can an area that is wet help prevent flooding? This is another way that wetlands ability to store water comes in handy. Think of a wetland like a sponge… when dry it is able to soak up large quantities of water and hold it. Sure a little might leak out into surrounding areas, but nowhere near the amount of water that otherwise would have without the absorbent landscape. For seasonal wetlands this is especially true, they are designed to soak up water during the wet winter and spring months, but are often dry during summer and early fall.

The water slowed down by wetlands also has more time to be absorbed. When wetlands are adjacent to rivers and streams, this slower movement helps it stay connected to areas that are better equipped to handle seasonal floods as was mentioned above. And who doesn’t love cleaner water?

Reason #3: Wetlands provide essential habitat

So this is the one that probably draws most people in… ESPECIALLY if they are birders. If you want to see some amazing wildlife, wetlands are probably a great place to start. Dominated by grasses, sedges, reeds, rushes, and trees like willows, these landscapes provide food and shelter for a lot of incredible species. Below are just a few of my local favorites:

1. Beavers – As an Oregonian, I feel like I have to start with our state animal. Best known for their dark chocolate brown coats, flat paddle-like tails, and bright orange teeth, these mammals are often the engineers of wetlands. While you might think of beavers gnawing their way through large trees that then come crashing down, most often they will remove lower branches or gnaw through parts of trees to get to the nutrient-rich cambium which they eat. Additionally, they will help new willows sprout so that they have access to a continuous food source. On walks around area wetlands, it is often much easier to find evidence like these.

Beaver are also often associated with the images of the dams and lodges they use to modify the environment around them. These mammals prefer water that is deep enough to create underwater entrances to their lodges – to avoid predators- but not too deep. When beavers move in and create a dam, it creates differences in water levels and often leads to some localized flooding. But this also means that the water slows down, leading to a build up of sediments. As these particles fill in the waterway, they can lead to prairies and eventually forests, making them a key part of local ecological succession. Their dams and lodges also help provide eventual shelter for a number of birds and other animals with which they have co-evolved.

Beaver are however crepuscular, meaning they are most active near dawn and dusk. There is evidence that this behavior is in response to avoiding humans or other predators as beaver in some areas with less predation are more active throughout the day. This means if you see a dark furry creature swimming around in the middle of the day, it is more likely a nutria or muskrat, which are often smaller and have skinny tails and light whiskers around their face.

2. Birds – Yes, I know it’s not a specific species, but the birding in and around wetlands is phenomenal. Watching a Great Blue Heron wade through the shallows in search of small fish or minnows very much makes think of what it must have been like to watch a dinosaur hunt. Or listening for the distinctive calls of Red-Winged Blackbirds or Belted Kingfishers while searching for that flash of red or blue.

Wetlands are also a great place to work on your life list as a birder. Many species make their home there year-round, but you’re also likely to catch a glimpse of migratory species as well. During a visit to the wetlands on Sauvie Island outside of Portland, I was able to see two new species: the Tundra Swan and Sandhill Crane. You can likewise watch a lot of fun bird behaviors, from nesting to foraging and everything in between, from larger birds like ducks and geese.

3. Rough-Skinned Newt – I love waiting for these little ones to become more active and move from the forest to the water. A rich brown topside, but with bright orange tummies, these salamanders are incredibly cute and much easier to find that many other local amphibians. Their coloration does make it easier for them to hide among damp brush, so you have to watch you step while in areas where they are active. They rely a lot on forests that are kept adequately moist throughout the year.

They often return to ponds or wetlands during March or April to mate and you might be luck enough to stumble upon a newt ball during these times. During their larval stage, they have gills that make them resemble darker hued axolotls.

But what many people know about the rough-skinned newt is that they are poisonous. They are able to secrete a tetrodotoxin in their skin, which allows them to avoid most predators. One notable exception is the common garter snake which has evolved a resistance to the toxin. And likely why you often see them in nearby habitats. When threatened, the newt while raise its head towards its tail, showing its bright orange belly. For these reasons (and generally respecting wild animals), it is a good idea to avoid handling rough-skinned newts and making sure to thoroughly wash your hands after doing so.

We Need Wetlands…And They Need Us Too

While it is very obvious that we and many others we share the planet with rely on wetlands, they need us too. In 2023, nearly half of previously protected wetlands in the United States lost that status under the Clean Water Act. These magical habitats need our protection now more than ever. And in the face of climate change, we might need them more than ever too. So this World Wetland Day, I encourage you to do you part: learn more about wetlands near you, help advocate for their protection, or support or volunteer with an organization helping to protect them and give wetlands a voice.